![]()

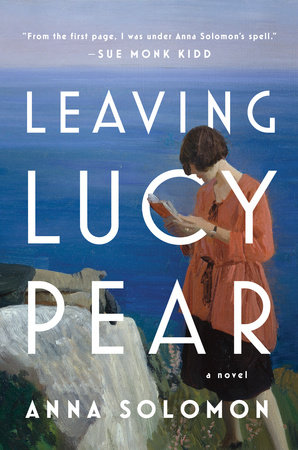

Leaving Lucy Pear is a hard book to categorize. It covers a large chunk of time and is told from several different points of view, yet it coalesces into a whole around an orchard of pear trees and a baby left underneath one of them.

The prologue shows us Beatrice Haven, age 17, who’s just given birth to a baby and is supposed to be giving her to the Jewish orphanage. Instead, she sneaks out of her uncle’s house one night and leaves her under a pear tree, knowing that an Irish family will be coming as they do every year to steal the pears, and hoping they steal her daughter as well. The plan is that this will leave Beatrice, a talented pianist, free to attend Radcliffe and ready for a glittering career and society marriage.

The reality, 10 years on, is that Beatrice struggles with depression, has formed a marriage of convenience with a gay man, and is just sort of lost. She returns to her uncle’s home to care for him. A series of coincidences lead to her hiring the Irishwoman, Emma Murphy, to help around the house, and the two women form a sort of wary relationship. Both are aware of the other’s secret, although neither understands that the other knows. Meanwhile, as we go deeper into Emma’s family, we see how dark-haired Lucy Pear fits in with her own fair-haired children, and begin to see the secrets that the girl is keeping from the adults in her life.

It’s 1927 in New England. Prohibition is creating political alliances on the one hand (between Beatrice and a wanna-be politician named Josiah, who is sleeping with Emma), and offering money-making opportunities on the other. Additionally, anti-Semitism is rampant, and Beatrice suffers the consequences when her depression and moodiness causes her to take steps to deal with a noise-making buoy, leading to a fatal boating accident.

It was fascinating to get such a deep glimpse into a decade I don’t know much about. We see the xenophobia of society in general, and the classism of the native-born versus the Irish or Italian immigrant. This was the era of working parties and strikes, when the owners of factories and quarries had to take a little more seriously the demands of their laborers.

Leaving Lucy Pear is very well done. The characters are deftly drawn, and so aptly described that you feel you might recognize them if you met them on the street. (I would know Beatrice anywhere!) The reader is taken into another world, one that is fully fleshed-out and knowable.